I once heard Maria Popova (of Brain Pickings / The Marginalian-fame) on a podcast –it was probably On Being with Krista Tippett – and one thing she said really struck me (and stuck with me):

Books are the original internet.

Apparently, this is an oft-repeated piece of Popovian insight. Here’s a little excerpt from a 2019 interview with the New York Times, where she says it again:

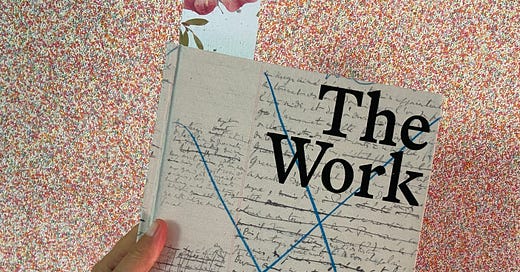

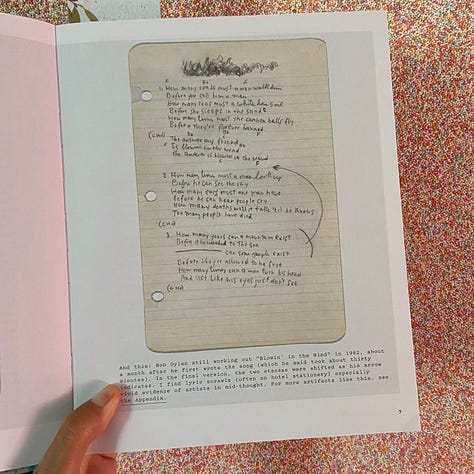

I’ve been thinking about the internet a lot recently, the way you can’t help but think of an elephant when someone tells you not to. That’s because I’ve been making an effort to stay off the internet, or at least limit the time I spend in the type of internet-consumption that is well-known to cause brain rot. I’ve done my best to replace my usual depressing scrolling sessions with deep dives into a single artefact from the original internet, a beautiful book called The Work of Art, How Something Comes from Nothing by Adam Moss.

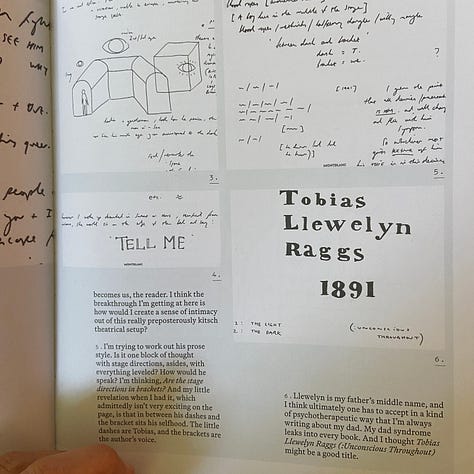

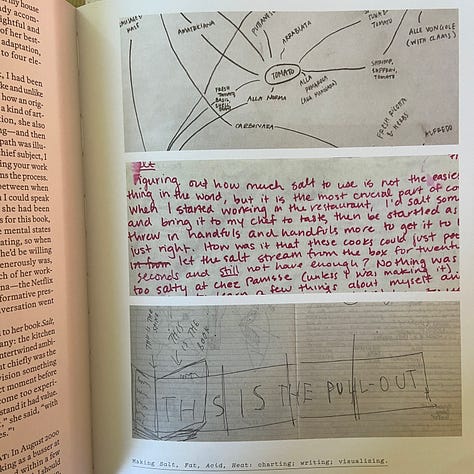

Moss is a former editor, most notably of New York magazine, and this background in the magazine world is evident in the innovative graphic design on display here.

I had been eyeing this book online for a while, and when I found a great story Moss wrote about Jonathan Franzen’s struggle to write The Corrections on Vulture, I was sold. I had to have it, even if it meant paying more for shipping and import tax than for the book itself. Friends, despite being relatively broke and feeling stressed about spending so much money on a single book, I have NO REGRETS.

It’s a delicious book. I am devouring it. It is adding a lot of spice to my life.

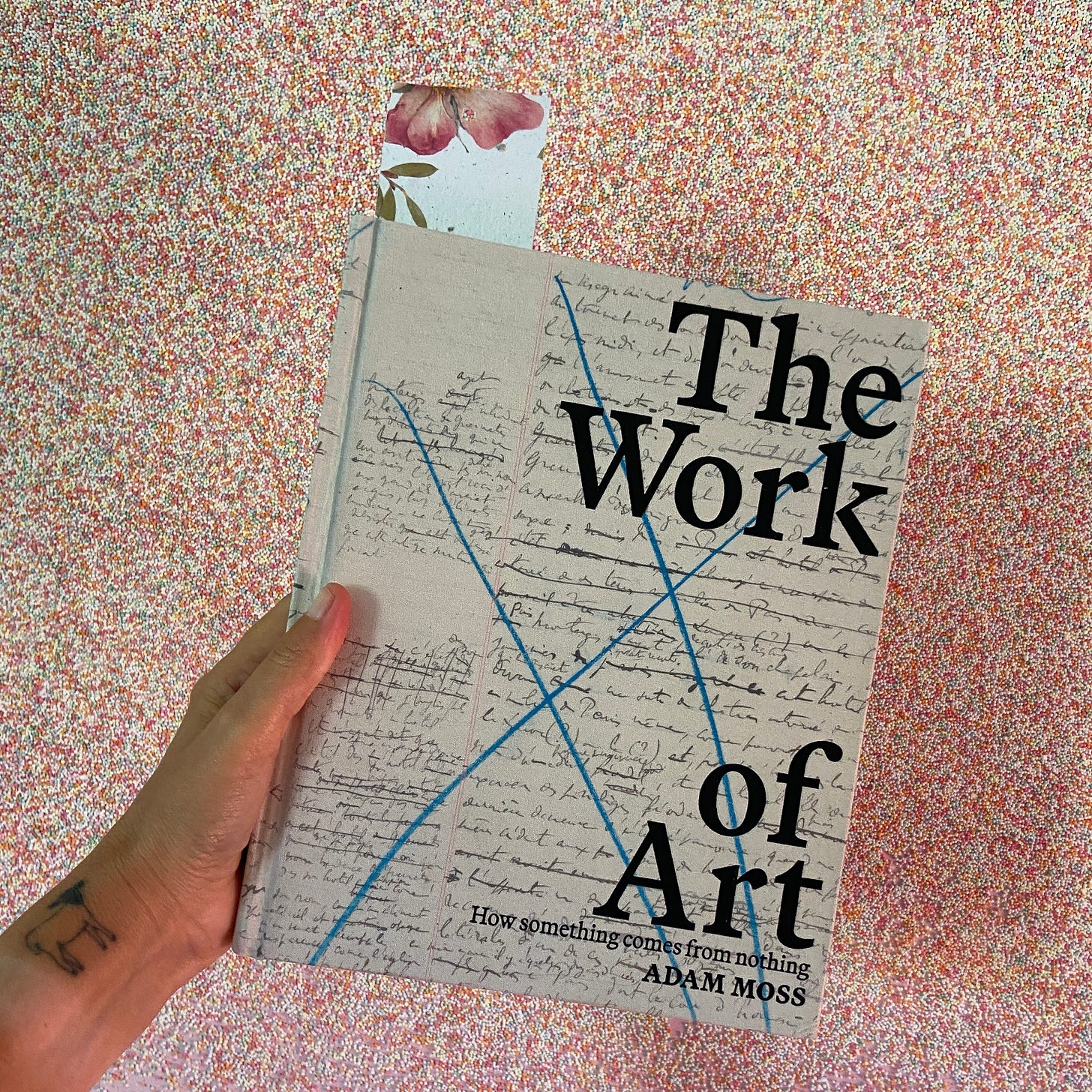

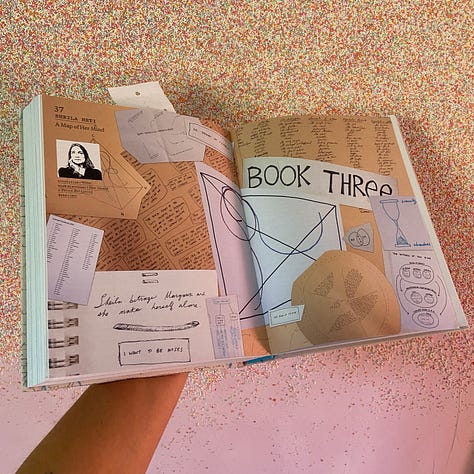

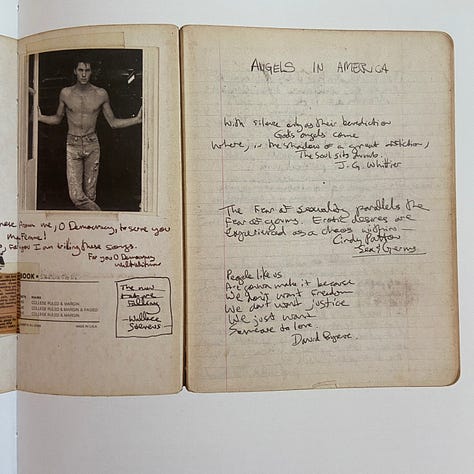

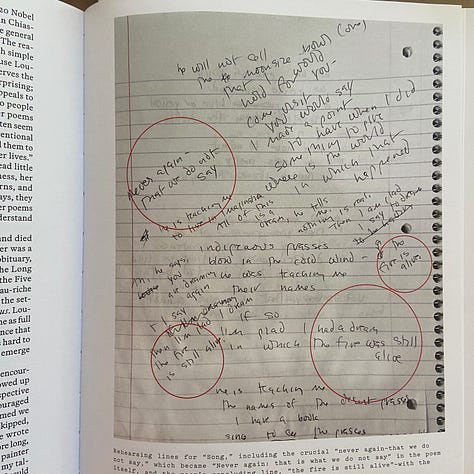

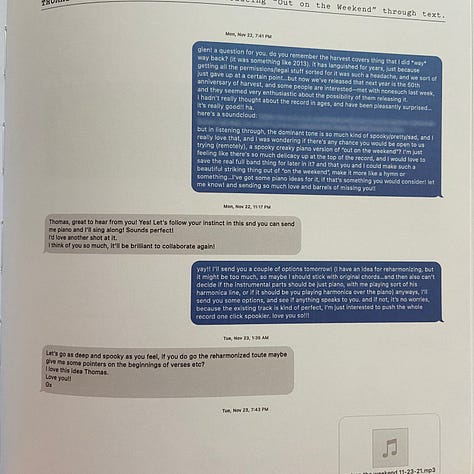

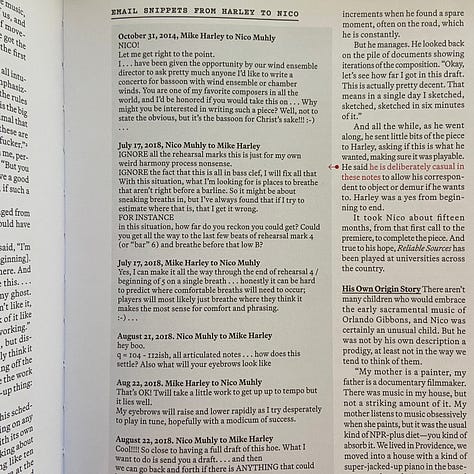

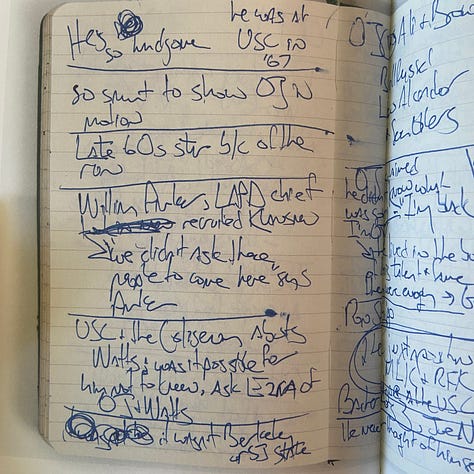

The Work of Art contains 43 case studies, complete with notes, drawings, photographs, emails, text messages, doodles and descriptions, documenting how specific works of art came about. It records the thinking before, during and after the making of, and provides captivating insight into the creative processes of poets, musicians, writers, comedians, critics, sculptors, painters, cartoonists and more.

I keep it on my bedside table and start my day with one of the case studies. I read another before bed. Sometimes, when the day needs a bit of juice, I’ll read one while eating my lunch, or reclining in my hammock.

I love how the book contains so many physical objects, and turns so much digital ephemera - emails, texts, weird little scribbles in the notes app – into something physically beautiful too. It’s also just been valuable to be reminded of the struggle, joy and worth of the process - how it is the same but different for everyone, how there is no one right way, and that the only way out remains THROUGH.

I’ve tried to treat it like the internet,allowing it to lead me to actual sensory experiences in the real world.

If you’re the type of person who might enjoy reading a bunch of Nico Muhly’s emails, allow the book to take you further along. Listen to a recording of the composition he is discussing as your read, find the work of the obscure composer he is influenced by, allow yourself to experience a whole stream of new-to-you things by following the crumbs. That’s how I’ve been using the book and it has created such a refreshing injection of cool shit. I’ve discovered the music of Doveman, which led me to songs by Ella Hunt. I’ve listened to songs from musicals I’d never seen (or even heard of), added Moses Sumney tracks from 2017 to my 2025 playlist, and sampled classic magazine journalism, like this piece by Guy Talese which I missed when it originally appeared in Esquire back in 1966. After reading the chapter on Michael Cunningham, I bought The Hours, which I somehow never read, as well as Virginia Woolf’s novel Mrs. Dalloway, as a fun little reading project for February.

Sure, books are the original internet, and they lead to other books, knowledge and wisdom. But they are also the original internet of things in the best possible way. Let a book take you into the world. Go see things, hear things and taste things based on where a book leads you. Really go where it suggests you go. Even if it’s not this specific book, I’m pretty sure another title will work in just the same way. As soon as I’m done with this one, I’ll try it again and let you know.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cunningham, Michael. The Hours. 1998.

Moss, Adam. The Work of Art - How something comes from nothing. 2024.

Woolf, Virginia. Mrs. Dalloway. 1925.

.